By PEGGY ORENSTEIN

March 10, 2009 in the New York Times Magazine

Someone I haven’t seen in decades just posted a snapshot of me on Facebook: there I am at 16, dressed in an unfortunate cowl-neck sweater, my hair cut to resemble a Semitic cotton ball. William Faulkner, I suspect, would love it — Facebook, after all, is the best evidence yet of the undead past. Ever since I signed up a couple of months ago, I have felt thrust into a perpetual episode of “This Is Your Life” (complete with commercials). “Friends” from nursery school have resurfaced, as well as high-school teachers (including the one who pinned me to a wall during a graduation party and slurred, “You’re not much to look at now, but when you’re 30 you’re gonna be terrific”). I have reconnected with the brother of a friend who was killed; rediscovered college chums and colleagues from my early days in New York. I am by turns amused, touched and horrified by these gentle breezes and icy blasts from the past.

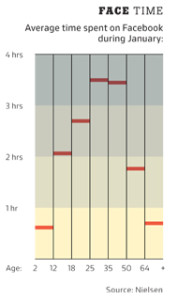

All of which is possible because I actually have one — a past, that is. As do most people my age, and apparently, we’re digging its excavation: there was an estimated 276 percent increase in Facebook users ages 35-54 during the last six months of 2008, bringing their total to almost seven million. Still, that number is dwarfed by the nearly 25 million users under 25. That gives me pause. They can’t be doing what we’re doing, right? What do they have to look back on? For all the discussion Facebook has prompted — over its “25 random things about me” narcissism, its mangled syntax (“Peggy is weekend”), the tricky politics of whom to friend (actual friends? strangers? “kinda knows”?) — its most profound impact may be to alter, even obliterate, conventional notions of the past, to change the way young people become adults.

Six of my nieces will head off to college over the next several years. Some have been Facebooking since middle school. Even as they leave home, then, they will hang onto that “home” button. That’s hard for me to imagine. As a survivor of the postage-stamp era, college was my big chance to doff the roles in my family and community that I had outgrown, to reinvent myself, to get busy with the embarrassing, exciting, muddy, wonderful work of creating an adult identity. Can you really do that with your 450 closest friends watching, all tweeting to affirm ad nauseam your present self? The cultural icons of my girlhood were Mary Richards of “The Mary Tyler Moore Show” and Ann Marie of “That Girl,” both redoubtably trying to make it on their own. Following their lead, I swaggered off to college (where I knew no one) without looking back; then to New York City (where I knew no one) and San Francisco (ditto), refining my adult self with each jump. Certainly, I kept in touch with a few true old friends, but no one else — thank goodness! — witnessed the many and spectacular metaphoric pratfalls I took on the way to figuring out what and whom I wanted to be. Even now, time bends when I open Facebook: it’s as if I’m simultaneously a journalist/wife/mother in Berkeley and the goofy girl I left behind in Minneapolis. Could I have become the former if I had remained perpetually tethered to the latter?

Online social networks are so new that it’s impossible to know their long-term impact. There’s some evidence that college students have mixed feelings about being guinea pigs for the faux-friendship age. One student interviewed for a study of why and how college students use Facebook, which was published last year in The Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, admitted that being privy to the personal details of “friends” who she had not seen in years made her uncomfortable. “Someone from earlier in her life had broken up with a boyfriend,” an author of the article, Sandra L. Calvert, a professor and chairwoman of the psychology department at Georgetown University, told me. “She felt she knew all these intimate details about this person, yet they hadn’t actually been in touch for five years.” On the other hand, a study published in 2007 in The Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication suggested that hanging onto old friends via Facebook may alleviate feelings of isolation for students whose transition to campus life had proved rocky. Evidently they took comfort in knowing that “Dylan is drinking Peets.”

That may well be, but something is drowned in that virtual coffee cup — an opportunity for insight, for growth through loneliness. Perhaps my nieces will find a new way to establish distance from their former selves, to clear space for introspection and transformation. Perhaps they will evolve through judicious deleting and updating of profile information, through the constant awareness of their public face. Maybe the Greek chorus of preschool buddies will be more anchor than albatross, giving them strength to take risks or to stick out tough times. It could be that my generation was the anomalous one, that Facebook marks a return to the time when people remained embedded in their communities for life, with connections that ran deep, peers who reined them in if they strayed too far from the norm, parents who expected them to live at home until marriage (adult children are already reclaiming their childhood rooms in droves). More likely, though, the very thing that attracts us oldsters to Facebook — the lure of auld lang syne — will be its undoing. Kids, who will inevitably want to drive a stake into the heart of former lives, may simply abandon the service (remember Friendster?) and find something new: something still unformed, yet to be invented — much like themselves.

Peggy Orenstein, a contributing writer, is the author of the memoir “Waiting for Daisy.”